What Decades of Data Reveal About Teen Loneliness That Headlines Often Miss - Spoiler Alert, It’s Not Just Technology

- The White Hatter

- Dec 14, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 4

Many parents and caregivers are increasingly hearing the claim that smartphones and social media are responsible for a loneliness epidemic among today’s youth. The argument is often framed as straightforward cause and effect. Teen loneliness has risen since the introduction of the iPhone, so smartphones must be the reason.

At first glance, that conclusion feels intuitive and emotionally logical, especially for parents and caregivers worried about the pace of technological change. The challenge is that this narrative depends heavily on selective data framing, rather than the full picture. (1) So our question was, “what does the good data have to share with us about this topic?”

One of the best cited sources in this discussion is the long-running U.S. study Monitoring the Future. (2) For decades, this study has asked 12th-grade students the same questions about their lives, including how often they feel lonely.

When data from 2010 onward is displayed in isolation, the trend does show an increase in self-reported loneliness among teens. This period overlaps neatly with the rise of smartphones and social media, which makes it easy to draw a straight line between the two.

However, what happens when we look further back? When researchers widen the lens, the story becomes more complicated.

Dr. Mike Males, a sociologist who specializes in youth and their use of technology, re-plotted the Monitoring the Future loneliness data not from 2010 onward, but from 1997 through 2024. (3) When viewed across nearly three decades, a different pattern emerges.

Teen loneliness was already high in the late 1990s. It was also elevated through the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s, long before smartphones, social media, or even widespread home internet access existed. In other words, adolescence has never been a loneliness free experience.

The most significant spike in loneliness appears during COVID, a period marked by school closures, social isolation, family stress, and disrupted routines. That increase makes sense given the circumstances and does not require technology as the primary explanation. We would argue that during the isolation of COVID, technology, especially online gaming, was one of the main ways we, especially youth, stayed connected as best we could during the pandemic. (4)(5)

As Dr Males stated,

"The change in high schoolers’ reporting loneliness – using a standard regression trendline to incorporate all years in the series instead of just cherry-picking the years that show what I want – is far below even tiny significance levels (d = 0.047, nothing), as the figures illustrate"

In plain english, when Dr Males full dataset is analyzed honestly, rather than selectively, the data does not support the claim that teen loneliness has meaningfully increased over time. The dramatic narrative only appears when certain years are isolated and framed without context.

Canadian Data Tells a Similar Story

In Canada, national loneliness data for youth aged 15 to 24 has only been collected since 2015. While the Canadian numbers do show elevated levels of loneliness in recent years, the graph closely mirror what we see in U.S. patterns (including during COVID) rather than contradict them, as mentioned above. (6)(7)

What we do not have in Canada is long-term historical data that would support the claim that loneliness was rare, minimal, or even higher before smartphones existed. However, we do believe that if we did have a historical record, like the US based “Monitoring the Future” report, it would likely show the same results.

Why Cherry-Picking Years Is a Problem

Cherry-picking data means selecting specific start and end points that support a preferred conclusion while ignoring the broader trend.

If someone starts their graph at 2010, the rise in loneliness looks dramatic and novel. If they start in 1997 or earlier, loneliness appears cyclical, persistent, and influenced by many factors beyond technology.

This tactic is common in what Dr Miles calls, “pop-academic debates” and media commentary. It is effective because most people do not have the time or tools to check what came before the chosen starting point. That does not mean the data is fake, it just means the framing is incomplete and taken out of context.

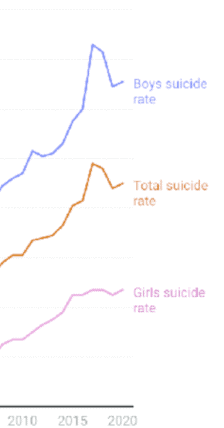

We have seen the same thing when some group report out that the rates of teen suicide have increased since 2010, again associating the introduction of cellphones as the “casual” link.

However, when we zoom out we see a more complete story that demonstrates that the levels of suicide in youth were actually greater when cellphones did not exits or were not common with youth and teens.

None of this suggests that teen loneliness should be dismissed. Feeling disconnected, isolated, or misunderstood is painful. Some forms of technology use can absolutely amplify those feelings, especially when they replace sleep, physical activity, or face to face relationships. So is loneliness a real issue for today’s youth and teens? Absolutely!, and we acknowledge that technology can contribute to loneliness in certain cases, and is not irrelevant.

However, what the data does not support is the idea that technology created teen loneliness or that today’s youth are uniquely broken compared to previous generations.

Other Factors We Need to Consider

Loneliness can be shaped by many overlapping confounding influences, including:

Academic pressure and performance expectations

Reduced free play and unstructured social time

Increased anxiety and mental health awareness

Family stress, economic uncertainty, and work demands

Changes in community design and extracurricular access

When we blame technology alone, we risk ignoring these broader forces and oversimplifying a complex human experience.

Instead of asking, “Did phones cause a loneliness epidemic?” a more useful question is:

“Under what conditions does technology deepen loneliness, and under what conditions does it support connection?”

That shift matters because it moves parents and caregivers away from fear based conclusions and toward practical guidance. It also respects what decades of data actually show. Adolescence has always included loneliness. Our role is not to eliminate technology, but to help our kids learn how to use it in ways that support real connection rather than replace it.

Facts and context matters when it comes to youth and their use of technology. When we widen the lens, the story becomes more honest and far more helpful for families trying to navigate the onlife world with their kids.

Digital Food For Thought

The White Hatter

Facts Not Fear, Facts Not Emotions, Enlighten Not Frighten, Know Tech Not No Tech

References: